| Investigación à Psicoanálisis |

Contribuciones

de la Epistemología, la Filosofía

y la Semiótica

a la Teoría de la Investigación en Psicoanálisis.

Semeiosis as a living process

Vinicius Romanini

viniroma@gmail.com

Introduction

Peirce´s theory of signs is not easy to grasp and there are a number of reasons for that. The most important is that it is unfinished. For nearly 40 years, Peirce actively worked on his system of logic he regarded to be the same as semeiotic. In these four decades, Peirce produced dozens of different definitions for the term “sign” and its fundamental aspects (which he called respects, probably meaning that they were always respective to one another, as in CP 8.343). The simple ones are quite similar because they involve only the three basic aspects and their correlation. So we can say without fear of mistake that a sign is anything that represents its object as to produce an effect, which is its interpretant.

But how these three aspects should be understood, eventually further divided and correlated to produce a whole system of logic, changed a lot in Peirce´s works. During his youthful years, his semeiotic was intended to cover primarily the relation between concepts — which he probably conceived just as symbols produced by human minds — and their objects. In his mature years, mostly after 1900, Peirce´s definition of sign was being continuously reformulated to incorporate his logic of relatives and his metaphysical musings about cosmology and a semeiotic theory of reality.Furthermore, Peirce found out that the three basic aspects described above in the basic definition should be decomposed into more subtle ones. The aspect of the object is then split into immediate and dynamic objects; and the aspect of the interpretant is thrice divided in immediate, dynamic and final. The myriad of possible relations among these now six aspects, as well as their ordering in a general classification of all possible classes of signs occupied Peirce´s mind until near his death in 1914.

We can clearly see from sketches drawn in his notebooks, as well as in his letters to Lady Welby and William James in the 1900’s, that Peirce spent the last years of his life working strenuously to reach the broadest possible definition for the word “sign.” In 1906 he even considered dropping the word “sign” and adopting the word medium, which seemed to him less contaminated with historical confusions. A “medium for the communication of a form” is then one of his preferred encapsulated definition for sign (EP II: 544, n.22).Another reason for the difficulty in understanding Peirce´s semeiotic is that it cannot be isolated from the rest of his philosophy. Quite the contrary, he considered his semeiotic as the cornerstone of his lifelong study of the scientific method to pursue the truth. Pragmatism or — as he sometimes preferred — “pragmaticism”, was his scientific method to clarify ideas by their consequences. A concept, or symbol, is a mental habit functioning as a conditional tendency to produce effects accordingly, and its meaning is the whole of the conceivable effects that it would produce in general conceivable situations. Since symbols must embody both indices and icons to produce reasoning, pragmatism should be considered a corollary of his semeiotic.

To catch the complexity of Peirce´s theory of sign, then, one needs to dive into the deep waters of this general, unfinished and many times idiosyncratic philosophical system in which metaphysics, phenomenology, philosophy of mind and logic would converge harmonically under his architectonic system. In the dawn of the 20st century, his theory of signs left the threshold of the human mind and culture to recognize that there is semeiosis whenever and wherever we find living systems. Putting together Plato´s idealism, Aristotle´s concepts of forms and final causes, Duns Scott´s medieval realism and Darwinian evolutionism, Peirce announces his “extreme realism” by saying that the whole of reality has the nature of sign, and semeiosis is akin to a fundamental theory of continuum (which he names synechism).Peirce was particularly worried about the direction science was going under mechanistic positivism, by which the explanation about observed phenomena was sought looking down into first [??] and discrete interactions of matter (1), instead of searching the final causes. In a letter of 1905, for instance, he claims that:

“to try to peel off signs & get down to the real thing is like trying to peel an onion and get down to onion itself, the onion per se, the onion an sich‘ (MS L387).

Some critics say that Peirce was advocating a sort of religious vitalism. Or that he was letting metaphysics dominate his thoughts as he got old, sick and worried about his death. Let´s not underestimate Peirce, though. He was a man of science, worked as chemist and physicist, knew mathematics as few of his time did, and was well read in philosophy of science. But first of all, Peirce was a logician and this grand vision of semeiosis should be understood as a statement about the foundations of logic and the pursuit of truth. His contribution to biosemiotics cannot be detached from these more general purposes.

A Peircean approach to biosemiotics

It has been often said that semeiosis is coextensive with life. I take this for granted, but also stress that this idea needs further development if we want to build a logical foundation for the field of biosemiotics. We can start by asking about the nature of such coextension. Viewing from a particular side, one can answer that semeiosis is a phenomenon emerging from life processes (2) which are considered primary. Taking the opposite perspective, another can say that life is the emergent phenomenon and semeiosis is the most fundamental.

A third and more profound hypothesis is that coextension might mean a continuous gradient by which life and semeiosis are two different words to signify the same thing: the creation of meaning, a process by which the real is produced as general representation developed by the continuous convergence of a multitude of interpretants (a concept which should no be equated to the action of interpreters made of flesh and blood, but more generally as a correlate of a logical triadic relation that can even be a simple possible effect of a sign.)

This last approach is the one I will develop here, which prompts me to add another concept that is coextensive both to life and semeiosis: mind (3). Putting it in a nutshell: life, mind and semeiosis might be just different words to describe the action of signs (or a genuine triadic relation, which amounts to the same). If that is the case, a truly Peircean approach to biosemiotics cannot escape from these considerations, although such a hypothesis must be also studied by the pragmatic method. That is, we should start by asking: What would be the conceivable normative practical consequences that we should establish in the scientific community of biosemioticians if we were to adopt the belief that mind, life and semeiosis are the same phenomenon viewed from different perspectives?

The first consequence is that we should not try escape from a metaphysical inquiry about the foundations of our concept of reality. Another consequence is that we should try to understand the minute aspects of the sign relations and how they would help us to understand biosemiotics as fundamentally the study of symbols as living signs (4). A taxonomy of all classes of signs and their logical relation is the necessary scaffolding for wrapping around the three concepts we are trying to weld into a single general and more powerful conception of reality. In the following pages we will give some hints about how we think these consequences could be taken into account, although much yet will be left for future research.

Peirce’s metaphysics

Following Kant’s Copernican revolution, Peirce early understood that our concept of reality is the result of a logical process by which the multitude of sense impressions given by perception are subsumed under a general concept produced a posteriori, or after the experience. This is done by the work of our mind, which is able to synthesize percepts due to the application of the concepts of space and time. For Kant, the thing in itself is not cognizable and reality appears as the arrangement of what is given during experience into space (giving us the outer sense of the world) and time (the inner sense of change and modality). The categories of space and time must then be a priori, which means that the conditions of possibility of any intelligible experience are built into our own human minds (5).

Having solved the enigma of the origin of our ideas in experience, Kant surrenders to an even greater mystery: how are pure sciences, such as mathematics and theoretical physics, possible? No one can deny that the theorems of geometry, the operations of arithmetic or the inductive method applied to physics bring us important practical results, but none of these are synthesized a posteriori. Neither are they analytical. They all seem to depend on a quite strange a priori synthesis. Without explaining this kind of knowledge we cannot justify causality, for instance. To say that the sun causes rocks to heat, (in general, that is, not only this or that rock but any conceivable one), would be meaningless, because we could only be sure of the heating of the particular rocks effectively subjected to our perception. We would never be able to suppose rocks in Mars are heated by the Sun unless we somehow actually measure them. Neither that a diamond is hard unless we actually scratch it (6).

Nevertheless, we all reasonably guess that any rock, be it on Earth or Mars, get heated when illuminated by the sun, or that a diamond will not be scratched by a knife. How can we justify such guesses – which are pretty much the kind of guesses that are behind any new discovery in science, the work of a geometer or of an artist? (7) In other words, from the very beginning of his studies in logic Peirce was interested in finding out how the human mind got its surprising ability to guess the laws of nature. He concludes that Kant had put a lock on the door of philosophy when he formulated the most important epistemological question ever made:

Kant declares that the question of his great work is “How are synthetical judgments a priori possible?” By a priori he means universal; by synthetical, experiential (i.e., relating to experience, not necessarily derived wholly from experience). The true question for him should have been, “How are universal propositions relating to experience to be justified?” (CP 4.92, 1893)

The answer Peirce attempts to give involves, in the first place, the denying of any uncognizable thing-in-itself. He assumes that everything is fundamentally cognizable because it participates in the whole of experience that springs from real possibilities. The “ding an sich” does not have a place in Peirce’s philosophical system because semeiosis is naturalized to explain mental and living processes, which are then considered to be of the same nature as a symbol. Only symbols can be used to express general conditional propositions and communicate the modal law they embody. Being indeterminate by their generality and bearing vague pregnancy (8) , symbols have a tendency to develop towards complexity by gaining information as they get more determined.

This is precisely the general mode of reality, as Peirce sees it: from the continuous flow of qualities of feelings underlying the real (with no clear cuts among them) unfolds the ever more clear and distinct attributes of reality. As they get determined, the work of mind (not this or that mind, but the communion of all possible minds) would eventually combine them by association so as to synthetically produce all types of complex beings (9).

Kant gives the erroneous view that ideas are presented separated and then thought together by the mind. This is his doctrine that a mental synthesis precedes every analysis. What really happens is that something is presented which in itself has no parts, but which nevertheless is analyzed by the mind, that is to say, its having parts consists in this, that the mind afterward recognizes those parts in it. Those partial ideas are really not in the first idea, in itself, though they are separated out from it. It is a case of destructive distillation. When, having thus separated them, we think over them, we are carried in spite of ourselves from one thought to another, and therein lies the first real synthesis. An earlier synthesis than that is a fiction. (CP 1.384)This implies that thought is a pervasive constituent of reality from which all kinds of predication are distilled, beginning at the level of sensation. The common mind of a community of interpretants then associate these seeds of ideas, or “semes,” (10)to produce cognitions and to represent them in general propositions which are then continuously reshaped and communicated to strengthen our common concept of truth:

This theory of reality is instantly fatal to the idea of a thing in itself, -- a thing existing independent of all relation to the mind's conception of it. Yet it would by no means forbid, but rather encourage us, to regard the appearances of sense as only signs of the realities. Only, the realities which they represent would not be the unknowable cause of sensation, but noumena, or intelligible conceptions which are the last products of the mental action which is set in motion by sensation. The matter of sensation is altogether accidental; precisely the same information, practically, being capable of communication through different senses. And the catholic consent which constitutes the truth is by no means to be limited to men in this earthly life or to the human race, but extends to the whole communion of minds to which we belong, including some probably whose senses are very different from ours, so that in that consent no predication of a sensible quality can enter, except as an admission that so certain sorts of senses are affected. This theory is also highly favorable to a belief in external realities. It will, to be sure, deny that there is any reality which is absolutely incognizable in itself, so that it cannot be taken into the mind. But observing that "the external" means simply that which is independent of what phenomenon is immediately present, that is of how we may think or feel; just as "the real" means that which is independent of how we may think or feel about it; it must be granted that there are many objects of true science which are external, because there are many objects of thought which, if they are independent of that thinking whereby they are thought (that is, if they are real), are indisputably independent of all other thoughts and feelings. (CP 8.13)

For the universe to be intelligible, generality must be a fundamental condition of reality, for only regularities are intelligible. These are what Peirce calls “thought,”his third category, or Thirdness. But no pattern is in a completely static and immutable situation. On the contrary, everywhere we perceive changes and the influx of novelty, which is Peirce’s first category, or Firstness. Experience, which is always hic et nunc, must involve intrinsic qualities which render it unrepeatable but must also be governed by some general patterns. The friction of experience is Peirce’s second category, or Secondness.

Now in genuine Thirdness, the first, the second, and the third are all three of the nature of thirds, or thought, while in respect to one another they are first, second, and third. The first is thought in its capacity as mere possibility; that is, mere mind capable of thinking, or a mere vague idea. The second is thought playing the role of a Secondness, or event. That is, it is of the general nature of experience or information. The third is thought in its role as governing Secondness. It brings the information into the mind, or determines the idea and gives it body. It is informing thought, or cognition. But take away the psychological or accidental human element, and in this genuine Thirdness we see the operation of a sign. (Peirce, CP 1.537, emphasis added)

Peirce does not rule out that there might be universes, even an infinite number of them, which are in a stage of pure firstness or eventually producing infinitesimal flashes of secondness. They might be all around us and have no consequence at all because they would not be reals. Continuity is what grants reality, which means that some sort of habit or law must be taken into account, although never so endured as to freeze changes and make growth impossible. Our Universe must have acquired the necessary generalizing tendency capable of governing replicas and growing towards complexity whenever novelty is internalized (11).If we want a scale, we could say that the more inveterate generals are the laws of nature that govern the so-called physical phenomena, followed by the much more plastic patterns of biological behavior of protoplasm, such as instinctive habits of actions and reactions. The more flexible habits are those of mental action, which are able to produce self-corrective habit-changes. Mental habits govern the inferences of reasoning by bringing forth their own possible future laws, which are the hypotheses that we create and entertain while shaping our conduct as to bring a harmonic sentiment of identity between the creations of our minds and the aesthetical feeling we gather from experience. That’s why minds are so much driven by iconic representation of possible relations, where mostly associations take place.

This finally solves the Kantian question of the possibility of every pure science, since all of them are based on diagrammatic representation of the laws of nature – that is, pure sciences represent a seme of the true functioning of the real, although never a complete truth about it. Reality, Peirce explains, has the form of a general capable of growth and development because animated by final causes, which are the general laws they embody and communicate. The synthesis of the multitude of percepts given by experience in the unity of a symbol is possible because the schema of time is not a transcendental entity, as Kant suggested, but is a regularity transforming and developing itself inside a living symbol:

The reality only exists as an element of the regularity. And the regularity is the symbol. (…) A symbol is an embryonic reality endowed with the power of growth into the very truth, the very entelechy of reality. This appears mystical and mysterious simply because we insist on remaining blind to what is plain, that there can be no reality which has not the life of a symbol.” (EP2: 323-324)

Some might think all this is an anthropomorphic view of Nature, which Peirce would promptly agree, for he considers this kind of anthropomorphism much better than anthropocentric illusion that reality is what it seems to be only because there are humans to observe it:I hear you say: “This smacks too much of an anthropomorphic conception.” I reply that every scientific explanation of a natural phenomenon is a hypothesis that there is something in nature to which the human reason is analogous; and that it really is so all the successes of science in its applications to human convenience are witnesses. (CP 1.316)

Putting it in simple words, when developing our science as an interpretation of natural processes we can only hope that the way our minds work has something in common with the way reality develops independently of ourselves. From this hope, which is a primordial hypothesis, we extract possible consequences and proceed to act accordingly. This means that the rationale of all reasoning is deductive at its bottom, although every ampliative inference produced during experience is either abductive or inductive (12).

Moreover, Peirce denies Cartesian intuition and Cogito to proclaim that perceptual judgments, in the guise of unconscious abductions, are responsible for producing fallible but self-corrective hypotheses that pave our path to the truth. Experience is the mother of all possible information and true knowledge is the information contained in that symbol which would be shared and agreed upon by an ideal community of interpretants.This would-be is the conditional law, or form, embodied by every symbol. This information might not be manifested to any actual mind but it is nevertheless real. This implicit or ‘unfolded’ form (13)is the foundation of Peirce’s so called scholastic realism and objective idealism. What is the meaning he gives, for instance, to the word “hard” when he describes the hardness as the predicate of a rock? Peirce explains:

(…) if he thinks that, whether the word “hard” itself be real or not, the property, character, the predicate, hardness is not invented by men, as the word is, but is really and truly in the hard things and is one in them all, as a description of habit, disposition, or behaviour, then he is a realist. (CP 1.27, n. 1)

Peirce conceived the whole of reality as a conditional argument from which general modality any number of particular world views could be derived, once more circumscribed communities of minds would develop, with their particular perceptive frames. As thirdness, the real is vague and indeterminate, but different degrees of determination can be accomplished by different living species, as the queries of reality are opened to their communicating minds.

Peirce’s logical conception of mind

One of the reasons some biosemioticians do not agree with Peirce’s metaphysics is that they understand thought and mind in their traditional Cartesian and folk psychological definitions. Peirce, quite differently, saw them as logical entities, as in this important quote from 1909:

All the various meanings of the word "Mind," Logical, Metaphysical, and Psychological, are apt to be confounded more or less, partly because considerable logical acumen is required to distinguish some of them, and because of the lack of any machinery to support the thought in doing so, partly because they are so many, and partly because (owing to these causes), they are all called by one word, "Mind." In one of the narrowest and most concrete of its logical meanings, a Mind is that Seme of The Truth, whose determinations become Immediate Interpretants of all other Signs whose Dynamical Interpretants are dynamically connected. In our Diagram the same thing which represents The Truth must be regarded as in another way representing the Mind, and indeed, as being the Quasi-mind of all the Signs represented on the Diagram. For any set of Signs which are so connected that a complex of two of them can have one interpretant, must be Determinations of one Sign which is a Quasi-mind. (CP 4.550)

It is a mistake of folk psychology to suppose that biosemeiosis depends upon individual agency, or upon a brain doted of some inexplicable intentionality. The semeiotic mind is not a product of brain activity, although a large brain might intensify and speed the process. Mind is simply a logical triadic relation producing and partaking of meaning, such as when we draw a diagram representing the relations conceived about the object of our inquiry and then proceed to transform these relations so as to reveal facts that were not noted before. For example, every living being participates in the instinctual search for the food that it needs to survive, and any particular hungry animal should be considered a particular instantiation of this very general and instinctual process happening throughout the living world.

The worldview of the species (what Uexkull called its Umwelt) is the diagram of all the relations concerned with its survival and permanence, while the actual manipulation of these relations is performed by particular specimens, or group of specimens living in community in a specific time and space. Whenever new hypothetic relations are discovered by chance during ontogenesis and internalized by the species as phylogenesis, we have the evolutionary working of mind reshaping the diagram of relations, producing co-evolution of both the living species and their own significant environment. Their immediate interpretants are deeply welded as their dynamic interpretants become dynamically connected in a habitual manner.

If it is true that any hungry living being feels the hunger and emotionally responds to this feeling, this only indicates that semeiosis is happening at a level near immediate perception, when feelings have not yet been generalized into cognitive processes capable of being shared. Emotions are insipient cognitions, produced inferentially to reduce the manifold of sensations gathered through perception into a single predicate – one capable of allowing a quick response to some sensitive situation.

(…) when our nervous system is excited in a complicated way, there being a relation between the elements of the excitation, the result is a single harmonious disturbance which I call an emotion. Thus, the various sounds made by the instruments of an orchestra strike upon the ear, and the result is a peculiar musical emotion, quite distinct from the sounds themselves. This emotion is essentially the same thing as a hypothetic inference, and every hypothetic inference involves the formation of such an emotion. (CP 2. 643)Peirce’s view of emotion connects it to organisms and their accidental situations (the ontogeny of individuals), while cognitions and sentiments are much more general and dependent on the development of instinct and the phylogenic development of species:

That which makes us look upon the emotions more as affections of self than other cognitions, is that we have found them more dependent upon our accidental situation at the moment than other cognitions; but that is only to say that they are cognitions too narrow to be useful. The emotions, as little observation will show, arise when our attention is strongly drawn to complex and inconceivable circumstances. Fear arises when we cannot predict our fate; joy, in the case of certain indescribable and peculiarly complex sensations. (CP 5.292)

Following this line of argument, our individual “self” must be considered the result of a flow of feelings, sensations and emotions, but which must sooner or later give place to a more general and mediated concept to be shared by a community of interpretants – a shared sentiment, which is the basis of Peirce’s sentimentalism: an instinct-like disposition to act in accordance to our past - or “collateral,” as we will see below – experience, without which no living being could ever communicate anything to his peers, his enemies or to any other participant of his ground.

In fact, without this continuous spreading of emotions into more community-like sentiments, no logical conception of reality would ever be possible, no learning and no memory would ever be produced. What we call instinct is just the repertory of all the past experiences lived by a community of living beings (a species, for example, but also any number of species that have a common past of shared experiences):

(...) every phenomenon of our mental life is more or less like cognition. Every emotion, every burst of passion, every exercise of will, is like cognition. But modifications of consciousness which are alike have some element in common. Cognition, therefore, has nothing distinctive and cannot be regarded as a fundamental faculty. If however, we ask whether there be an element in cognition which is neither feeling, sense, nor activity, we do find something, the faculty of learning, acquisition, memory and inference, synthesis. (CP 1. 376)

As much as we see growth and information in every corner of the Universe, so we notice that even the most ingrained instincts can develop as living species experience the flow of reality:

Instinct is capable of development and growth -- though by a movement which is slow in the proportion in which it is vital; and this development takes place upon lines which are altogether parallel to those of reasoning. And just as reasoning springs from experience, so the development of sentiment arises from the soul's Inward and Outward Experiences. Not only is it of the same nature as the development of cognition; but it chiefly takes place through the instrumentality of cognition. The soul's deeper parts can only be reached through its surface. In this way the eternal forms, that mathematics and philosophy and the other sciences make us acquainted with, will by slow percolation gradually reach the very core of one's being; and will come to influence our lives; and this they will do, not because they involve truths of merely vital importance, but because they are ideal and eternal verities. (CP 1.637)

To sum up, meaning is a matter of general relations that evolve on the level of species or, more generally yet, on the level of the whole biosphere. That’s why Peirce says “even plants make their living… by uttering signs.” (MSS 205, 318). Every living species must be considered, as a whole, a cognitive repository of learned experiences, and its metabolism – as well as any of his more complex functions – are communicative utterings necessarily attuned to the patterns and laws that govern reality. Here echoes again the Kantian challenge about the possibility of a priori synthetic inferences and Peirce’s answer: the inward and outward senses are indeed the ground of all instinctual inference, but there are not a priori. They are the ground of the intelligible reality, the very common ground of every living species.

A white blood cell of our immune system moving after bacteria in a way that resembles a cat chasing a mouse (14)is not a solitary bunch of blind physical and chemical reactions, but a marvelous example of semeiotic conduct towards a definite, if only instinctual, purpose. Without this broad conception of mind, we would have to bring into the action of the white cell the finger of a magical divinity, or disguise biosemeiosis in some strange theory similar to the Cartesian homunculus.

Take it all or leave him alone

Biosemioticians embarrassed by Peirce´s extreme realism and synechism prefer to skip such ideas and use only the excerpts where Peirce deals only with semeiotic terminology. Others prefer to learn Peirce´s doctrine of signs second-handedly through commentators that have hidden Peirce´s objective idealism under the carpet. In both cases, the pervasive mentality that bathes reality becomes the hidden variable of Peirce´s theory of signs. Both options lead invariably to huge mistakes. I will give you a concrete example. One of the most famous and quoted definitions of the “necessary and sufficient condition for something to be a semiosis” — found in dozens of articles, books and papers on biosemiotics — was given by Posner, Roberick and Sebeok:

A interprets B as representing C.In this relational characterization of semiosis, A is the interpreter, B is some object, property, relation, event, or state of affairs, and C is the meaning that A assigns to B. (Posner et al., 1997, p. 4)

I am not saying the above is necessarily wrong. The authors in question have all the right to propose their own definition of sign and semeiosis. My question is: is this definition in accordance with Peirce´s semeiotic? Let´s see.

In Peirce´s terminology of the triadic relation among sign, object and interpretant, when the above authors say that “A interprets B as representing C” we must understand that A is the place of the interpretant, B is “some object, property, relation, event, or state of affairs” that functions as the sign and C is the object being represented. Paraphrasing in a somewhat tautological expression we have kept the original definition in italics and added Peirce´s three basic elements of his triadic definition in capital letters:

INTERPRETANTS (A) interprets SIGNS (B) as representing THEIR OBJECTS (C).So far so good. But we get into muddy waters when the authors define C as “the meaning that A assigns to B.” That is wrong in Peircean semeiotics.

If by C we understand the dynamic object, that is, the object which the sign professes to represent because it conveys some information about it, then C cannot be the meaning of semeiosis in Peircean terms because meaning is for Peirce just another name for the interpretant of the sign:A ’sign’, I say, shall be understood as anything which represents itself to convey an influence from an Object, so that this may intelligently determine a ‘meaning’, or ‘interpretant.’ (MS 318, 1907)

The problem I am raising is not a mere technicality. Putting the meaning of a sign under the realm of the interpretant is the kernel of Peirce’s theory of signs and pragmatism. Indeed, the pragmatic maxim states that the ‘entire meaning and significance of any conception lies in its conceivably practical bearings’ (EP: 145), that is, the effects and consequences of accepting the truth of such sign under conceivable circumstances.

If we simply equate meaning and the object of the sign, we slip into nominalism. Peirce would turn over in his grave if we were to transform his semeiotic into a nominalistic enterprise. What is missing, then, in the definition given above? Final causation, for interpretation is a teleological process of production of effects through the action of signs, or semeiosis. (15) Putting this in semeiotic terms, we cannot explain reality, or mind, or life or any other process in nature if we do not admit final causation based on the process of the transmission of forms from the dynamic object to interpretant through the sign.The quoted authors put the action of semeiosis in the interpreter, when it should be in the sign. Semeiosis means “action of the sign” and not “action of the interpreter.”

But how is such active transmission of form actually done?Collateral experience

The answer is given by Peirce himself in the lengthy quote at the head of this chapter: the action of the sign in any cognitive semeiosis is responsible for calling the attention to the form of the dynamic object, but leaving to the interpreter the work of finding out what is being signified.

(…) the Dynamical Object (…) the Sign cannot express, (…) it can only indicate and leave the interpreter to find out by collateral experience.” (A Letter to William James, EP 2:498, 1909)

Here we come to a central feature of Peirce’s theory: collateral experience, through perception, grounds semeiosis (16). The sign can only denote its dynamic object by making evident some relation that, although already familiar in a very vague and general way, was kept hidden in the background until now. But what is precisely this collateral experience?

(…) by collateral observation, I mean previous acquaintance with what the sign denotes. Thus if the Sign be the sentence “Hamlet was mad,” to understand what this means one must know that men are sometimes in that strange state; one must have seen madmen or read about them; and it will be all the better if one specifically knows (and need not be driven to presume) what Shakespeare’s notion of insanity was. All that is collateral observation and is no part of the Interpretant. But to put together the different subjects as the sign represents them as related — that is the main [i.e., force] of the Interpretant-forming. (CP 8.179)

Collateral experience is responsible for producing the necessary familiarity with the dynamic object for the sign function as such. The form that inhabits the sign, or the immediate object, not only grounds semeiosis but is also responsible for transforming pure blind indexes into cognitions. Through knowledge accumulated by perception and stored in memory, semeiosis offers the necessary predicate to ground the meaning of immediate interpretants, putting semeiosis into movement and producing information (17).

A common example used by Peirce to illustrate this process is the weather-cock: as it rotates driven by the wind, it blindly points to some direction, but this is a blind index that brings no information in itself. Familiarity about the way a weather-cock works, gathered by collateral experience, will enable the association between the form of the movement made by the weather-cock (an iconic representation of the direction the wind is blowing), and its pointing to a specific direction. Information is then produced (see CP 5. 138 and CP 5.287, for instance.)The solenoid of semeiosis

The usual representation of the sign relations simply puts the aspects of sign, object and interpretant at the vertices of a triangular figure. To my wit, Peirce has never drawn such triangles and their appearance was probably due to Ogden and Richards (1923). The insistence in applying this triangle to represent semeiosis is the cause of great mistakes, and biosemiotics has become contaminated with them. In this section I provide my own model for the flow of information as the sign develops toward its final interpretants.

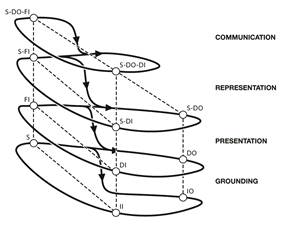

The solenoid of semeiosis (see figure above) is a recursive torus organizing the sign aspects and their possible relations into four periods. Its recursive logic resembles the Smale-Williams attractor, the Moebius strip, the Klein bottle and other autopoietic-like, recursive, flows of information. (18) The solenoid is (Romanini, 2006):

- Dynamic: it behaves like a dynamic system built from recursive interaction. The great system of semeiosis can be divided into smaller sub-systems. This nesting of systems creates dynamical hierarchies. (Collier, 1999)

- Periodic: it shows a periodical flux. By periodicity we mean the phenomenon of repetition of a group of properties at steady intervals (Scerri, 1998), although there is an increase of complexity in the whole.

- Autopoietic: it is autopoietic (Maturana and Varela, 1980), that is, it produces itself from a fundamental complementarity between structure and function.

- Ampliative: it develops from the simple and goes towards the varied and complex, that is, it moves towards the increase of information.

One continuous arrow goes botton-up and shows the order of determination among 11 aspects (19) of the sign: this means that a genuine and habitual triadic relation (generality in the relation sign, dynamic object and final interpretant: S-DO-FI) implies that the immediate object (IO) is also a general (this is so as well with every other intermediary aspect of the solenoid). Conversely, if the immediate object is a mere possibility, then the relation S-DO-FI will necessarily be a mere possibility (as well as every other intermediary aspect of the solenoid of semeiosis).

Aspects of the grounding period

IO (Immediate Object): In living systems, it is the non-conscious flow of quality of feelings that grounds the real; in mental semeiosis, it is the “idea,” “form” or “seme of the truth” about the dynamic object that any sign must embody to be able to represent the dynamic object. In the final true opinion held by an ideal community, such immediate object would become “the real” (20). Since fallibilism forbids truth from being ever fully reached, the immediate object is always somewhat metaphoric, i.e., an approximation. In physical systems, it can be considered the multiple entangled states expressed by an amplitude of probabilities. It is internal to the sign.

II (Immediate Interpretant): the non-conscious effect of a sign. In living systems, it ranges from emotions to quasi-automatic bodily effects. In mental semeiosis, it is perceptual judgment and the set of already established meaning of a symbol (as expressed in a dictionary, for instance). In physical systems, it can be the meaningful “decoherence” of multiple possible states of the immediate object. It is also internal to the sign. It is a symmetry-breaking that produces habits.

S (Sign itself or representamen): it is the phaneron, or what appears as phenomena to the mind, before it can represent anything else; “a medium for the communication of a form”; whatever can be noted by living systems; the “furniture” of reality as the result of perception; the manifested reality resulting from decoherence; the present as it appears to be related to the past and to produce the future. Its tendency is to develop toward the final interpretant, which is its intended future. A habit governing the representamen, and consequently the period of grounding, produces the worldview (not only of individuals, but of communities and species).

Aspects of the presentation period

DO (Dynamic Object): it is whatever the sign professes to represent, but can only imperfectly do. In physical systems, it can be regarded as the “past” information; in living systems, it is the pattern or information that must be gathered, or the “objective” environment. This bears some further explanation: we know that the light coming from a distant star tell us about its past, but the same must be said of the environment around a living being or species: an animal smelling food is getting information from its surrounding past. In any informational flow, the dynamic object is the “utterer” of the information (form) to be communicated by the sign.

DI (Dynamic Interpretant): the actual effect produced by the action of a sign; in living systems, it is the manifestation of its behavior, for instance; in physical systems, the sequential change of states of any dynamic system.

FI (Final Interpretant): what every sign would become if all its possibilities of signification were totally fulfilled. The ideal future of the sign, its entelechy, the apprehension of all the information the sign is capable of communicating; the final general state towards which any system tends. As the final interpretant is a normative parameter, but never actually fulfilled, semeiosis is necessarily fallible. A habit governing the final interpretant, and consequently the period of presentation, produces legisigns. In genuine classes of signs, if the sign (S) is thirdness and the final interpretant (FI) is secondness, we have replicas. If both S and FI are secondness, we have sinsigns. When they are both firstness, we have qualisigns.

Aspects of the representation period

S-DO (relation between the sign and its dynamic object): the nature of the relation between a sign and its object; as the sign develops, its power to function as a medium improves.

S-DI (relation between the sign and its dynamic interpretant): the nature of the relation between a sign and its dynamic interpretant.

S-FI (relation between the sign and its final interpretant): the nature of the relation between the sign and the final interpretant. In genuine classes of signs, if there is a habit governing this aspect, and consequently the whole period of representation, we have symbols. If the aspect S-DO is governed by thirdness and the aspect S-FI is secondness, we then have replicas. If both the aspect S-DO and S-FI are both secondness, we have indexes. If they are both firstness, we have icons.

Aspects of the communication period

S-DO-DI (relation among the sign, its dynamic object and its dynamic interpretant): the actual dynamic communicative action of the sign; the realm of assertions and of all kinds of performative speech acts. The actual sharing of the form of the dynamic object as to produce a communicative effect. The actual performance of a mating ritual, for instance.

S-DO-FI (relation among the sign, its dynamic object and its final interpretant): the logical realm of propositions and arguments; the normative final upshot of any communicative enterprise. The final purpose (reproduction) guiding a mating ritual, for instance. A habit governing this aspect, and consequently the period of communication, produces arguments. In genuine classes of signs, if there is thirdness in the relation S-DO-FI and secondness in the relation S-DO-FI, we have inductions. If both S-DO-DI and S-DO-FI are secondness, we have dicisigns. If they are both firstness, we have rhemas.

These four periods are closed when there is habit dominating all the aspects they involve, which means that novelty and new information becomes increasingly irrelevant. In the limiting case, if these resulting habits are so rigid as to block the possibility of novelty in the whole solenoid, we have what is usually called the laws of nature (21). In this case, the habitual forms governing semeiosis are those we identify by geometry and which allow the deduction of mathematical theorems. This is the kind of causation we experience in phenomena such as gravitation and acceleration (22), where feelings are almost totally absent. If the lawfulness of the generated habits is less rigid, novelty pops up as feelings and we have life-like purposeful behavior shown by protoplasm (CP 6.259 and ff.), such as metabolism and instinct (23). Eventually, vague and general habits become smooth and fluid by information generated during sensations, which we then identify as mental semeiosis (24). In actual semeiosis, though, we have none of these extreme limits, for no law of nature is so determined as to eliminate every possibility of unpredictable results (which would amount to a probability of 1/1), nor is any real phenomenon so free from regularity as to be absolute novelty (which would then amount to a probability of 0/1).

The grounding period, which is the most fundamental one, is closed into recursive loops only when there is generality in the aspects of the immediate object (IO), immediate interpretant (II) and the representamen or sign in its materiality (S). Whenever habit is not totally established in this period, we experience active perception, which is the non-conscious production of general predicates by collateral experience. When habit becomes inveterate in the grounding period, perception is not the relevant activity anymore, and knowledge production decreases. It is what happens when we get bored by something and stop paying perceptive attention to it. The grounding period produces whatever is immediately present to the mind: the non-conscious phaneron, the flow of feelings, the perceptive, and active, continuum of information that connects the real (which is very similar to David Bohm’s non-local, implicit although active information, real but nonetheless waiting to be manifested during experience).

The presentation period, which is the second of the solenoid from the botton-up, is closed only when there is habit dominating the aspects of sign (S), dynamic object (DO) and final interpretant (FI). If habit is ruling this period (which implies that habit is also ruling the more basic grounding period), when the manifestation of the phaneron as consciousness: the world is disentangled from our subjectivity and becomes “objective” due to the habitual manifestation of the dynamic object. The sign itself (S) develops into the general final interpretant (FI), creating legisigns, which are the laws that effectively rule the manifested world. Inveterate habits in this period produce a complete regularity of manifested phenomena, which is commonly taken as the “furniture” of the world: rocks, rivers, clouds, wind-blows, animals, people. If the grounding period produces perception, the presentation period produces inquiry, which is simply the act of questioning the rules that govern the manifested reality.

The representation period, which is the third of the solenoid from botton-up, is closed when habit dominates the aspects of the relation between the sign and the dynamic object (S-DO), the relation between the sign and the dynamic interpretant (S-DI) and the relation between the sign and final interpretant (S-FI). If rigid and inveterate habit dominates this period (which means that it also dominates the two previous ones), attention is not paid to the manifested “objective” reality anymore, but to what it represents. An actor on stage representing Hamlet presents his own body to the public but represents the fictional character created by Shakespeare. But to be effective such representation must count on the public collateral experience of what is being represented in a very general and vague way. That is to say, the public must have a grounding (a familiarity gained by a continuous flow of feelings) about Hamlet in such a way that what is being staged is welded to what the public already know about kings, madness, vendetta, cruelty etc (25). In this period we have deliberative semeiosis, because the act of representation encompasses a great degree of freedom, since collateral experience varies greatly among different minds or communities of minds. We can easily prove this by the many possible ways political representation can be established in different countries and in different historical periods according to different culture, influences, etc.

The communication period, which is the forth and last of the solenoid of semeiosis from the botton-up, closes when we have habit ruling the relation among sign, dynamic object and final interpretant (S-DO-FI). This necessarily implies that the relation among sign, dynamic object and dynamic interpretant (S-DO-DI) is also habitual, as well as all previous periods of the solenoid. If rigid habit rules this period, we have law-like communication. The most rigid habitual communication is the physical transmission of information from past to future (the so-called light cone), but the gradient of possible flexibility of communication is enormous, as the chemical communication of substances, the organic communication of living organs, the instinctual communication among species. If communication is freely self-organized, we have the scientific phase of semeiosis: through a rhetoric based on the scientific inquiry, a community of minds welded by a common purpose, or commens, endeavors to share meaning and reach mutual persuasion on the basis of evidence gathered through perception. Peirce calls it methodeutics, the science of communication when the pursuit of truth and the revelation of reality is the only guiding desire. This commens is a logical entity and must not be confounded with only the union of all human minds at every time. It is the communion of all possible minds active in the Universe, of which we might be a tiny sample.

The solenoid applied to biosemiotics

One interesting feature is that the rationale of the solenoid of semeiosis could be used to build a taxonomy of the living being based purely on their cognitive capabilities. The lower levels of mental complexity exhibit habit-taking only in the grounding period, where perception is active. The next level, one period above, shows habit-taking in the presentation level, where the world appears as a regular pattern of events. Only the most complex types of living-beings show habit formation in the representation and communication periods, where the work of abstractly produced signs, capable of being shared among living and freely cooperative specimens, become predominant. That would mean that not only ontogenesis and phylogenesis are acting to create the complexity of the living, but also the more fundamental process of semeiosis, which could here be called semiogenesis (26).

Genuine triadic relations as expressed by the solenoid of semeiosis are easily found in living systems. A hungry dog sniffs the smell of food in the air and follows its path. The dog is a specimen of a species, which means that much of his behavior is an expression of general instinctual modes of living developed during the phylogenetic evolution of its species. The smell is the sign that denotes the existence of food (its dynamic object) and immediately produces an effect (an emotion, such as an excitation and desire to follow the smell), which is the immediate interpretant. This happens only when its concentration on the environment reaches a level sufficiently high as to be perceptible by the olfactory apparatus of the dog, becoming then able to indicate to the animal that food is nearby.

If this kind of smell embodies mainly a quality of the food, its concentration must be a fact of perception, a difference in the environment that the dog must be able to note. On the other hand, the smell can only function as a sign because the dog has some habitual or pre-dispositional familiarity, usually instinctual, with the fact that eating that food represented by the smell-sign will satisfy him. This familiarity must be gotten through previous experience by which a particular kind of smell becomes significant to a canine species during its evolution. This is collateral experience on the level of evolution, a phylogenetic collateral experience. In conclusion: qualitative properties working as icon, an environmental concentration working as index, and a previous familiarity or habitual instinct working as symbol are all intertwined in semeiosis to produce a purposeful action.

But the dog is not after the smell. It is after the food or, more correctly yet, he is after the feeling of satisfaction that he would get after eating the food. This is the final interpretant or purpose of his following the path of the smell. The smell, as a sign, is just a medium by which the food – represented in the smell-sign in its pattern of qualitative odor – has the potentiality of affecting the dog’s behavior: the action of moving and sniffing around, always correcting its trajectory to keep himself in the direction from which the smell is coming – which are all dynamic interpretants.

The habitual relation between the appearance of smell-sign in the dog’s phaneron and its dynamic object (the relation sign-dynamic object) is granted by habit: in order to survive every dog must be able to relate a kind of smell to the kind of food he needs to eat. His actually accomplishing this relation in order to act accordingly is granted by habit in the relation between the sign and the dynamic interpretant (sign-dynamic interpretant), and the security that the same would happen whenever the dog is hungry and is exposed to the same kind of smell is granted by habit in the relation between the smell-sign and the fulfillment of the purpose of getting food (relation sign-final interpretant).

The whole process involving the dog searching and getting the food it needs to survive is a semeiotic communication between the dog and the reality its species is determining as it evolves. This continuous flow of communicative actions, by which every dog of this species gets food while co-influencing the significant environment where it lives and aims to continue to live, is the relation sign-dynamic object-final interpretant (S-DO-FI). Each of these acts performed by a particular dog is expressed by the relation sign-dynamic object-dynamic interpretant. This means that every species is in continuous communication with its significant “Umwelt,” even if only instinctually, when the purpose is survival.

There is no doubt that signs get their meaning by deep and mostly unconscious processes of perception, but semeiosis can also produce conscious and rationally self-controlled purposeful actions. A particular dog cannot prevent himself from feeling hungry (which is the result of unconscious mental activities), although it can be taught not to jump on a table to get the food there but wait until the food is served in the pot by the master. Learning is a marvelous example of purposeful semeiosis because it involves habit-taking or the modification of old habits, even deep instinctual ones, by the introduction of self-controlled behavior expressed by new habits. This is possible only when true reasoning of a diagrammatic type takes place to produce a breakdown of inveterate symmetries and the production of new ones.

In fact, a diagrammatic process must take place by which the master makes evident to the dog the habitual bad consequences of jumping on the table, as well as the habitual good ones of waiting to be served with food in his pot. This diagram must embody a set of syntactical general relations involving the dog, the master, the food, the table, the pot and the treats and punishments the dog effectively gets (dynamic interpretants coordinating the actions of the master and the dog) according to the purpose of the learning (final interpretants). To be effective, learning must be a process involving the unconscious generation of a new hypothesis (perceptual judgments or habitual immediate interpretants — the pleasures and displeasures at stake), the evidence of some of the consequences extracted from the new hypothesis (deduction) and the continuous satisfaction of acting according (dynamic interpretants) to the new hypothesis, producing an induction leading to final interpretants. Peirce gives us an example from daily experience with his dog Zola where a similar process is described:

I tell my dog to go upstairs and fetch me my book, which he does. Here is a fact about three things, myself, the dog, and the book, which is no mere sum of facts relating to pairs, nor even a pairing of such pairs. I speak to the dog. I mention the book. I do those things together. The dog fetches the book. He does it in consequence of what I did. That is not the whole story. I not only simultaneously spoke to the dog and mentioned the book, but I mentioned the book to the dog; that is, I caused him to think of the book and to bring it. My relation to the book was that I uttered certain sounds which were understood by the dog to have reference to the book. What I did to the dog, beyond exciting his auditory nerve, was merely to induce him to fetch the book. The dog's relation to the book was more prominently dualistic; yet the whole significance and intention of his fetching it was to obey me. In all action governed by reason such genuine triplicity will be found. (CP 2.86)

In the above example of semeiosis given by Peirce, we easily notice that the periods of representation and communication are not instinctual but contingently produced by the relation between the dog and his master and dependent on diagrammatic reasoning involving abductions, deductions and inductions.

An example from David Bohm

I want to finish this chapter with an example of learning extracted from Bohm and Peat (1987) that might offer some important lessons in this epoch of too much audiovisual semeiotic analysis. Although starting from a different road, the quantum physicist David Bohm came to similar conclusions about the ontological status of reality (27). As is known, Bohm´s interpretation of quantum mechanics proposes the reality of a peculiar implicit, non-manifested field of information bathing the whole of reality, and which becomes manifested or explicit as particles of matter during perceptive processes such as measurements. Bohm describes this kind of active information as being like the form of the streams of oceans and rivers in the manner in which they make particles behave the way they do. Like Peirce´s information that brings life to the real, Bohm´s form has mindlike properties and depends on the wholeness of a communicative process carried out during the experiment. And like Peirce´s participatory theory of communication, Bohm´s theory of meaning also depends on perception and communication.

Bohm illustrates his own hypothesis with the case of Helen Keller (1880 –1968), a deaf and blind girl from early age who not only was contemporaneous with Peirce, but whose process of learning how to communicate happened precisely in the same years Peirce was developing his semeiotic theory of meaning and communication. When Peirce died in 1914, Helen was 34 and had already earned a degree of Bachelor of Arts, had become an author of books, lecturer and political activist. Helen’s destiny changed when Anne Sullivan accepted the job of privately teaching the little girl. She did not realize that she was to find a “wild animal” that could not communicate. Bohm explains how Sullivan managed to teach Helen Keller:

The key step was to teach Helen to form a communicable concept. This she could never have learned before, because she had not been able to communicate with other people to any significant extent. Sullivan, therefore, caused Helen, as if in a game, to come into contact with water in a wide variety of different forms and contexts, each time scratching the word water on the palm of her hand. For a long time, Helen did not grasp what all this was about. But suddenly, she realized that all these different experiences referred to one substance in many aspects, which was symbolized by the word water on the palm of her hand. (…) Thus, the different experiences were implied in some sense as being equal by the common experience of the word water being scratched on her hand. (…) Up to that moment, Helen Keller had perhaps been able to form concepts of some kind, but she could not symbolize them in a way that was communicable and subject to linguistic organization. The constant scratching of the word water on her palm, in connection with the many apparently radically different experiences was suddenly perceived as meaning that, in some fundamental sense, these experiences were essentially the same. (Bohm and Peat, 1987, pp.36-37)

Here is another wonderful example of semeiosis bringing life to a concept. The patterns we usually associate with water (which are the dynamic object to be represented) have a number of regular characters, such as fluidness in its liquid state, a certain average temperature ideal for drinking, an evocative sensation of pleasure when we drink being thirsty, another sensation when we bathe etc. These general properties are as real as the hardness of a rock we previously discussed. They can be learned by non-conscious perceptual judgments if we are exposed to them through our senses. The possible cognitive patterns of predicates (the general feeling of fluidness of water, the general cooling temperature when drinking it etc) are the immediate objects of the sensation. The possible emotional effects produced by the sensation of the qualities of water are their immediate interpretants.The English word “water” was invented by men. It is a legisign grounded by the information brought by the community of its users - including the teacher Ann Sullivan - and animated by a form of significance, which is a teleological component. But how can we manage to relate the word water scratched on the palm of the hand of someone who does not know its meaning to the bunch of real properties held by the substance water? Simply by putting them into continuous association, side by side, in a multitude of occasions, until a synthetic inference is created.

Guided by Ann Sullivan, Helen produces a series of collateral experiences initially unrelated but that are mentally associated by the scratching of the same word “water” on the palm of her hand. The scratching itself produces some sensations as a regular form is drawn, when immediate objects and immediate interpretants connected to the scratching are also unconsciously gathered. The continuity of experience between the sensation of water and the sensation of scratching produces a common ground between them both, while bringing them into relation. Not only the scratching becomes the sign of the flow of qualities of feelings we usually identify with water, but the familiar patterns of those past qualities of feelings stored in memory becomes the dynamic object to be represented. They are then welded by the tendency of mind to produce a more general pattern resulting from their unification.

When the sequence of scratchings is felt as a regular pattern by Helen Keller (a legisign), it becomes for her a symbol of the general qualities of feelings she experienced collaterally when in perceptive contact with the substance water. Here begins the relation sign-dynamic object (S-OD), which is consolidated at the almost magical moment when the girl Helen, feeling thirsty, takes the hand of her teacher Ann and scratches a similar form on the palm, putting the relation S-DO to an actual use (the relation sign- dynamic interpretant, or S-DI). This is done with a clear purpose: asking for those pleasant qualities of feelings that will bring her painful thirst to an end, which is described by the relation sign-final interpretant, or S-FI, when purposeful representation between Ann Sullivan and Helen Keller becomes habitual. A concept is born.

As we have already seen, a concept, or symbol, is precisely a mental habit capable of communicating the form of the dynamic object so as to produce general interpretants in a conditional future. This communication happens whenever Ann, Helen or any other person of a community of users of the word “water” effectively uses it to reach pragmatic effects. Utterances made in particular contexts (contingent and therefore emotionally grounded) are assertions depending on the relation among the sign, dynamic object and dynamic interpretant (S-DO-DI). If I am walking on a desert land and a stranger comes to me and says “water” with a weak and suffering voice, I am emotionally inclined to take it as a begging. If I am distractedly walking on the seashore and suddenly see someone pointing to the sea while shouting “water”, I am inclined to interpret it as a warning of something dangerous such a huge wave coming towards me. All the habitual manners in which a community of users would employ the word “water” to reach pragmatic purposeful effects (esthetic, ethical and logical ones) involve the relation among sign, dynamic object and final interpretants (S-DO-FI). It is the communicative sum of all lessons to be learned from it.

Conclusion

Biosemiotics is an emergent, even effervescent interdisciplinary field of research that promises to bridge the gap opened in biology when it chose a too-materialistic approach by following the path taken by chemistry and physics. This line of research led to important discoveries about the functioning of metabolism and the role of specific molecules in organisms. But the description of living processes is not all that biology is about. It is also about understanding how life itself is possible and how biological processes can produce evolution, consciousness, meaning, representation and communication. Biosemiotics is the branch of biology interested in understanding life as semeiosis, where meaning and interpretation play the central role. Applying Peirce’s theory of signs to biosemiotics will certainly help the development of biosemiotics, but it might equally help the development of Peirce’s proposal for a logical theory of reality. His admonishment for a logically grounded metaphysics to deal with the vital questions of life must be taken into consideration by biosemioticians. There is even a sense in which semiotics and biosemiotics are synonymous, for semeiosis was considered by Peirce a genuine triadic relation of the same nature as that of living processes. If this would prove correct, advancing Peirce’s theory of signs is also advancing biosemiotics. This was the motivation of this chapter, which has certainly not fulfilled all that is needed to reach a complete taxonomy of all possible classes of signs and their mutual relations, but nevertheless took the risk of proposing an interpretation of Peirce’s mature and very complex theory of signs in terms of biosemiosis. While this chapter only opens a narrow trail by explaining how the solenoid of semeiosis can be applied to living processes, I think there is a large road to be completed in this same direction. The scientific question about the biological meaning of life and the metaphysical question about the logical meaning of life might have, at the end, the very same answer.

Notes

(1) This led Peirce to an interesting semeiotic version of the quantum uncertainty principle: “But as soon as a man is fully impressed with the fact that absolute exactitude never can be known, he naturally asks whether there are any facts to show that hard discrete exactitude really exists. That suggestion lifts the edge of that curtain and he begins to see the clear daylight shining in from behind it” (CP 1.172). He would have regarded as pointless the search for fundamental quantum particles and would have instead exhorted physicists to search for the logical causational principles governing reality.(2) Sebeok (2001), for instance, says that “semiosis presupposes life”.

(3) My frame of interpretation is similar to Ivo Ibri’s definition of connaturality of mind and matter. See chapter 2.

(4) See chapter 8 by Winfried Noeth for an explanation of the life of symbols.

(5) Jakob von Uexkull used this same line of argument to create his concept of Umwelt, which is basically a generalization of the Kantian system to all living beings: “No matter what kind of quality it may be, all perceptual signs have always the form of a command or impulse. If I claim that the sky is blue, I am doing so because the perceptual signs projected by myself give the command to the farthest level: Be blue! The sensations of the mind become, during the construction of our worlds, the qualities of the objects, or, as we can put it in other words, the subjective qualities are building up the objective world. If we, instead of sensation or subjective quality, say perceptual sign, we can also say: the perceptual signs of our attention become the perceptual cues (properties) of the world.” (Uexkull 1973 [l928]). Peirce would regard this as an unattainable nominalistic view of perception.

(6) Peirce himself fell into this sort of nominalism in his early writings, as he himself admits in CP 5.453 and later on, in CP 5.457, correcting his own mistake, he explicitly declares that “we must dismiss the idea that the occult state of things (be it a relation among atoms or something else), which constitutes the reality of diamond's hardness can possibly consist in anything but in the truth of a general conditional proposition.”

(7) See the quote from CP 1.383 that illustrates Vincent Colapietro’s chapter 6.

(8) See Robert Lane’s Chapter 3 for an excellent treatment of vagueness and indeterminacy in Peirce’s philosophy.

(9) See CP 1.383, as well as Vincent Colapietro’s explanation about this synthesis in Chapter 6.

(10) CP 4.538-9: “Of course, I must be understood as talking not psychology, but the logic of mental operations. Subsequent Interpretants furnish new Semes of Universes resulting from various adjunctions to the Perceptual Universe. They are, however, all of them, Interpretants of Percepts. Finally, and in particular, we get a Seme of that highest of all Universes which is regarded as the Object of every true Proposition, and which, if we name it [at] all, we call by the somewhat misleading title of ‘The Truth.’”

(11) “The tendency to obey laws has always been and always will be growing. We look back toward a point in the infinitely distant past when there was no law but mere indeterminacy; we look forward to a point in the infinitely distant future when there will be no indeterminacy or chance but a complete reign of law. But at any assignable date in the past, however early, there was already some tendency toward uniformity; and at any assignable date in the future there will be some slight aberrancy from law. Moreover, all things have a tendency to take habits. For atoms and their parts, molecules and groups of molecules, and in short every conceivable real object, there is a greater probability of acting as on a former like occasion than otherwise. This tendency itself constitutes a regularity, and is continually on the increase. In looking back into the past we are looking toward periods when it was a less and less decided tendency. But its own essential nature is to grow. It is a generalizing tendency; it causes actions in the future to follow some generalization of past actions; and this tendency is itself something capable of similar generalizations; and thus, it is self-generative. We have therefore only to suppose the smallest spoor of it in the past, and that germ would have been bound to develop into a mighty and over-ruling principle, until it supersedes itself by strengthening habits into absolute laws regulating the action of all things in every respect in the indefinite future.” (CP 1.408)

(12) (...) although Abductive and Inductive reasoning are distinctly not reducible to Deductive reasoning, nor either to the other, nor Deductive reasoning to either, yet the rationale of Abduction and of Induction must itself be Deductive. All my reflections and self-criticisms have only served to strengthen me in this opinion. But if this be so, to state wherein the validity of mathematical reasoning consists is to state the ultimate ground on which any reasoning must rest". (Peirce in Turrisi, 1997, p 276-277)

(13) As David Bohm (2000) puts it.

(14) I owe this example to Daniel Meyers (University of San Diego).

(15) For a better understanding of Peirce’s semeiotic theory of causation, see Chapter 5 by Hulswit and myself.

(16) See Chapter 7 by Quilici and Silveira for a relation between collateral experience, information and instinct.

(17) The semeiotic information could be identified with Fisher’s information, which is dependent on an amplitude of probabilities. In Frieden and Romanini (2008), we show that this amplitude might express the resultant of a community of interpretants and is the effect of measurements made (and registered as signs) about a parameter (the dynamic object.)

(18) See, for instance, Roy Frieden 2004 (2000).

(19) Peirce identified 10 aspects of the sign, but did not ruled out the possibility of more (CP 8.343 : “... I do not say that these divisions are enough…”). In fact, I found out the need for at least one more: the relation among sign, dynamic object and dynamic interpretant, which is important to logically differentiate between assertions (what is effectively said, as a question, order, doubt etc) and propositions (the informed relation between subjects and predicates, which is the intellectual pattern expressed by a dicissign). Assertions are dynamic utterances dependent of contextual and emotional accidents, while propositions are general conditionals expressing universality.

(20) As Peirce explains, “the immediate object of thought in a true judgment is the reality.” (CP 8.16)

(21) CP 6. 25: “The one intelligible theory of the universe is that of objective idealism, that matter is effete mind, inveterate habits becoming physical laws. But before this can be accepted it must show itself capable of explaining the tri-dimensionality of space, the laws of motion, and the general characteristics of the universe, with mathematical clearness and precision; for no less should be demanded of every philosophy.”.See Ivo Ibri’s Chapter 2 of this volume for a full exposition of this doctrine.

(22) In fact, Peirce puts both gravitation and acceleration under the general law of causation, as Peirce explains in CP 1.270 and CP 6.68.

(23) CP 2.170: “If I may be allowed to use the word "habit," without any implication as to the time or manner in which it took birth, so as to be equivalent to the corrected phrase "habit or disposition," that is, as some general principle working in a man's nature to determine how he will act, then an instinct, in the proper sense of the word, is an inherited habit, or in more accurate language, an inherited disposition. But since it is difficult to make sure whether a habit is inherited or is due to infantile training and tradition, I shall ask leave to employ the word ‘instinct’ to cover both cases.”

(24) For an excelent treatment of Peirce’s concept of habit, see Chapter 4 by Eliseo Fernandez.

(25) “When the universe of discourse relates to a common experience, but this experience is of something imaginary, as when we discuss the world of Shakespeare's creation in the play of Hamlet, we find individual distinction existing so far as the work of imagination has carried it, while beyond that point there is vagueness and generality.” (CP 4.172)

(26) In fact, Peirce says that “Genesis is production from ideas. It may be difficult to understand how this is true in the biological world, though there is proof enough that it is so.” (EP2:127)

(27) Brent (1993) was one of the first Peirce scholars to point out the similarity of views between them.